Check out our latest products

![]()

Photographer Mario Heller’s unique story is that of a baker turned photographer through his love of storytelling and photojournalism.

Mario Heller is a Berlin-based Swiss documentary photographer whose award-winning visual narratives provide a rare glimpse into the human experience of remote and often extremely isolated communities.

Taking time away from his busy schedule, Heller spoke with PetaPixel a look into his photographic philosophy and latest photo project, Arctic Dreams, centered around the people of Barentsburg, Norway.

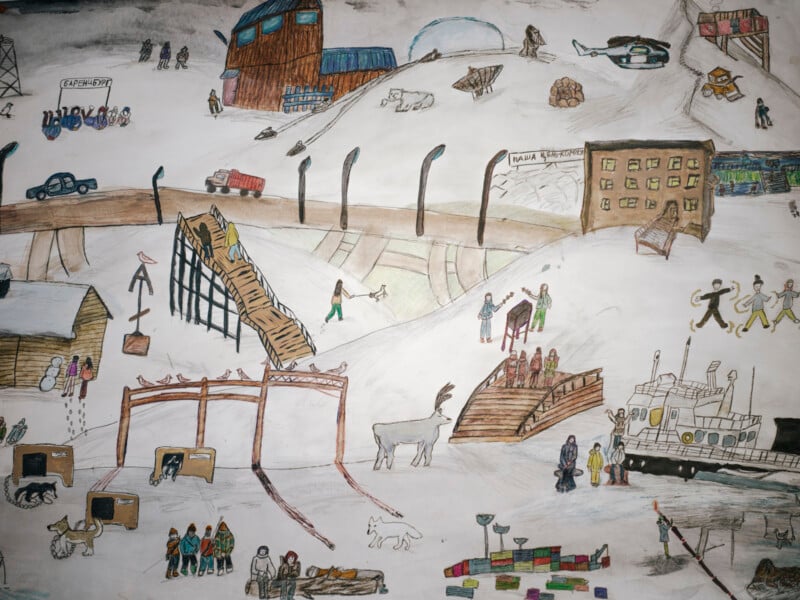

“There is a tradition in Barentsburg. When you go to the mainland, you hug a tree because there are none here. The Russian enclave on Spitsbergen in the Arctic is so remote that you only reach it by helicopter, snowmobile, or ship. Because of the danger of polar bears, leaving the village without a rifle is forbidden. In winter, Barentsburg sinks into months of darkness; in summer the sun shines around the clock,” Heller describes.

“The population consists primarily of Ukrainian miners and young urbanites from Russia. They live in a close-knit community where everyone knows each other. Who are the people who have chosen to live in this strange place? And how do they manage to coexist peacefully in times of political tension?”

Heller’s photography not only looks to answer these questions but also shines a light on this extremely isolated, unique settlement whose population hovers around 400.

However, in seeking to answer questions about the people on the other side of his lens, it also gave him insight into himself. Heller has always had a passion for storytelling, writing page-long crime stories as a child and experimenting with a photo blog; he dreamed of combining his two passions with photojournalism, telling stories with his imagery. However, the realities of life bring their own negativity. To make ends meet he worked as a pastry chef, saving up all of his money until he could apply to journalism school.

Unfortunately, while in school he faced negative feedback from the program director. However, with personal growth his self-reflection led to not only learning from feedback but also understanding his strengths and weaknesses, preventing the common issue of plateauing that some artists and creatives often face.

“I vividly remember the interview where the program director warned me that ‘nobody is waiting for you’ and suggested my money might be better spent elsewhere. Despite this, I persisted and completed the one-year course, which not only refined my technical skills but, more importantly, connected me with industry professionals,” he shared.

“Afterward, I interned at a local newspaper, learning to work under pressure and developing my portrait photography skills. Looking back at those images now, I’m often embarrassed by their quality and my stubborn resistance to feedback. I mistakenly thought it was a strength to “do my thing” and give photo editors as few options as possible, believing I needed to maintain control.”

This autonomy and initiative means that Heller’s work has a singular style and voice, however, he’s learned the hardest tool is not your camera but that of patience.

“I favor centered, symmetrical compositions. To me, a photo series is like a piece of music. It needs an opening, a refrain, and a finale. It requires rhythm. You want to capture people in their activities while also including portraits and meaningful details,” he mused.

“My creative process is primarily self-directed. While I’ve consumed countless photobooks and listened to many photographers’ perspectives, perhaps adopting elements here and there, I’ve learned that your approach must work uniquely for you. Developing something truly distinctive takes enormous time and patience. It must be tailored to your vision and sensibilities.”

However, patience in creating one’s vision has its own rewards. Heller described how he mentally organizes his work by thinking of them using a rating system of one to five stars. This balanced amount of self-criticism helps him stay on track and create work that will capture photo editors’ attention, even on tough days in the field. Crucial to his success is not allowing frustration to get in the way but persevering and being ready for the five-star moments.

Heller explained, “During a day of reportage, I might only produce common, one-star photos. This can be frustrating, draining, and test my patience. Then suddenly, a five-star opportunity emerges from nowhere. You need to anticipate it, be prepared to capture it, and never let it slip away.”

It is the chase of five-star moments that led Heller to his photo series exploring such remote cultures and communities. He loses himself for hours exploring Google Maps, researching countries that he’s never heard of, strange borders, and remote islands. Hours turn into weeks as he reads articles, listens to podcasts, watches videos, and learns as much as he can about locations that inspire him.

A tip that he’s found especially useful is reaching out to locals through social media for help, first to even find out whether a location is accessible, then opening the door to discovering fixers, local guides, and even translators when necessary. Having a trusted network of dependable locals has proved crucial in overcoming challenges such as obtaining access to locations, uncovering interesting stories, and also in not appearing to be a lone outsider therefore opening the door to wary subjects.

As a father and part-time photo editor, Heller allocates seven to 14 full days of focused work for his personal documentary projects. He’s found through experience that this is the perfect amount of time for him to develop a coherent storyline. Furthermore instead of feeling daunted by his responsibilities to his family, it gives him direction towards focusing on only the locations that he feels most inspired by.

“Russia and the Soviet Union play an important role in many of my stories. I’ve traveled to several former Soviet states like Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Tajikistan. I’m fascinated by the legacy of this period, both good and bad. I tend to seek out stories that aren’t necessarily urgent. I wouldn’t go to war zones or photograph suffering. Instead, I look for appealing everyday situations that reveal something about people’s lives,” he says.

To create a work that feels full and tells the story of someone’s life in less than two weeks means that Heller’s process including gear has to be on-point. There is no room for faulty equipment when you are in such remote locations, far from repairs or rentals. Heller describes himself as a self-proclaimed tech nerd who after trying a variety of cameras by different manufacturers has settled on his dream kit through experience and understanding his needs.

“I’ve probably tried every major camera brand. For instance, I attempted to become a Leica M photographer two or three times, always appreciating the camera and its philosophy but ultimately finding that manual focus made me miss too many shots and left me frustrated,” Heller explained.

“In 2022, I found my dream camera: the Hasselblad X2D 100C. Since then, I haven’t looked elsewhere. I use my Nikon Z6 II for most assignments and my Hasselblad for all personal projects. This distinction matters to me, as shooting with the Hasselblad remains a special experience. I exclusively use it with the 38mm XCD 2.5 lens, which helps maintain consistency across my series.

“In my opinion, photographing should be fun. It should be enjoyable. Like a piano player wants to play on a nice piano, a photographer wants to photograph with a nice camera.”

As many photographers can relate, one’s heart becomes full with a sense of accomplishment when you have created work that you just know is special. Heller is especially proud of his Arctic Dreams series, which he described as one of his best projects.

To create it he used his formula of photographing with gear that he enjoys, researching the area in full, setting up that crucial network of a team of locals, and applying his skills and experience to telling the story of the people who call Barentsburg home.

“I spent 14 days in Barentsburg, a Russian mining settlement on Spitsbergen, which actually belongs to Norway. Since the Soviet era, Ukrainians and Russians have lived together in this village. When I discovered this on Google Maps, I immediately knew it was special,” Heller says.

“I contacted the coal mining company there, and they were incredibly helpful. I visited in winter, and they gave me access to their helicopter. They opened every door for me, allowing me to work without supervision, which is remarkable considering the mining company’s close ties to the Russian government.

“The approximately 400 inhabitants were incredibly welcoming. After just a few hours, they integrated me into their daily lives, inviting me into their homes and greeting me on the street. Since it was February, the sun had just returned after more than three months of near-complete darkness, creating incredibly special light conditions. It made creating the project almost effortless.”

The results are a body of work that, in his signature symmetrical rhythmic style, capture not only people in their daily activities but also meaningful portraits and imagery of the town itself, its unique visuals breaking up the stark snowy landscape, truly frozen in time.

With the conclusion of this work that has meant so much to Heller, he returns renewed and inspired to continue exploring isolated places and sharing their stories with the world.

Heller said, “I continue to explore isolated places most people would never visit, absorbing the stories of those who live there and sharing them with a broader audience. This mission will always drive me, and it’s something AI will never truly replicate. While AI could easily generate images of the most remote places on Earth, they will always remain fabrications, never capturing how uniquely incredible human reality actually is.”

Mario Heller’s writing and photography can be seen on his website, full of compelling projects from Pamir Stoics, Last Stop: Narva, to Kazakhstan Time Travel and others full of narrative and visuals combining his love of photography and the written word, he continues to weave the threads of a tapestry telling the story of forgotten places.

Image credits: Mario Heller

![[2025 Upgraded] Retractable Car Charger, SUPERONE 69W Car Phone Charger with Cables Fast Charging, Gifts for Men Women Car Accessories for iPhone 16 15 14 13 12, Samsung, Black](https://i1.wp.com/m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61SaegZpsSL._AC_SL1500_.jpg?w=300&resize=300,300&ssl=1)

![[True Military-Grade] Car Phone Holder【2024 Stronger Suction & Clip】 Universal Cell Phone Holder for Car Mount for Dashboard Windshield Air Vent Long Arm Cell Phone Car Mount Thick Case,Black](https://i2.wp.com/m.media-amazon.com/images/I/715PBCuJezL._AC_SL1500_.jpg?w=300&resize=300,300&ssl=1)

![[エレコム] スマホショルダー ショルダーストラップ 肩掛け ストラップホールシート付属 丸紐 8mm P-STSDH2R08](https://i3.wp.com/m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51BMFf06pxL._AC_SL1500_.jpg?w=300&resize=300,300&ssl=1)