Check out our latest products

![]()

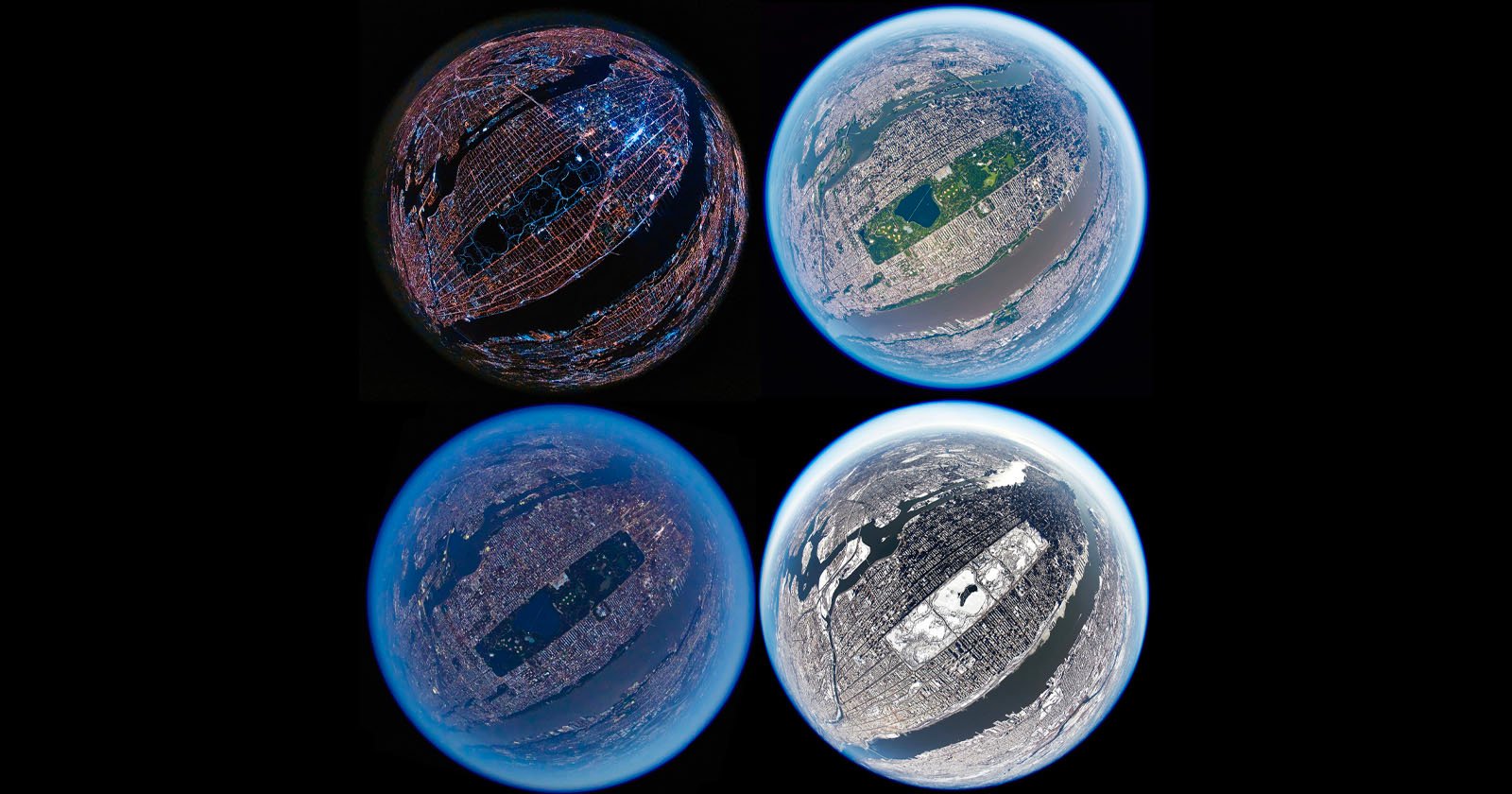

Back in 2015, a question popped into my head during a weather hold at a New Jersey helicopter hanger: “Could you capture the entire island of Manhattan in a single image?”

A quick Google revealed some composite frames and a few fixed-wing high-altitude versions. I decided to go a different route. Canon had recently released their 8-15mm fisheye zoom, and at its widest, this lens captures a perfectly circular image with a 180-degree field of view on a full-frame sensor. I picked up a used one on eBay and popped off a few frames as a test during an event coverage flight at 3500ft. I guessed that double that altitude might be able to fit all of Manhattan inside the fisheye circle and with the help of my friends at FlyNYON, I quickly found myself hanging out of an A-Star over a snowy Central Park on a frigid February afternoon.

The first attempt was successful, and I got the green light to try a night version a few weeks later. It was unsurprisingly much colder, and miraculously,y I avoided massive motion blur from the high winds and 1/60 second shutter speed. I did a quick color pass and export as we thawed out in the hangar, and I moved onto the next project.

I’ve been moonlighting as an aerial photographer and have flown with FlyNYON for well over 10 years at this point. I started out shooting stock and eventually moved into real estate/commercial photography and event coverage. Some jobs were 4 AM wheels-up, sub-zero temperatures rendering my fingers barely able to push the shutter release. Others found us high over MetLife Stadium with fireworks streaking across the sky during the Star Spangled Banner or with a 400mm lens trained at a group of yoga participants in Times Square.

I popped off a few rolls of Aerochrome 120 in an RZ67 in between locations on a real estate shoot and was lucky enough to be in the air during the Macy’s Fourth of July fireworks show. All in all, good fortune has allowed me quite a bit of experience in a harness, feet dangling above the city. Many of these gigs took place before drones made aerial imagery accessible to the masses.

I’m not anti-drone by any means (I regularly use them on my film projects and have a part 107 license), but there were a few reasons I went with back helicopters as I finish this series.

First off, NYC has incredibly restrictive drone laws. They are essentially banned by the city from flying in all five boroughs (with the exception of a few designated model aircraft fields) without an NYPD permit. Said permits for takeoff and landing cost $150 to request (no refund if rejected), need to be filed at least 30 days in advance, have rules like requiring notices about the flight to be publicly posted, and are always subject to change. And that’s before you’ve considered all the FAA laws regarding flying over a city of 8.25 million people and 4 major airports nearby. And here’s the kicker: I need to be at 7,000+ feet over Central Park for this image to work.

![]()

Once there is an agreement about our timeframe for the flight, there are several technical considerations for this project. First, the positioning of the helicopter is vital, and you need to be able to communicate with the pilot. The problem here is that it’s incredibly windy at this elevation, so any live feed microphone you wear would flood the line with wind buffeting. Push-to-talk would technically work, but I usually need both hands for the camera operation. We decided to have someone sit kitty-corner from me, whom I direct via hand signals, and they communicate directly with the pilot. This allows the pilot to hover directly over the target (the baseball diamonds south of the reservoir in this instance) until I’m confident we have the shot.

![]()

Fortunately, the final image is circular and can thus be rotated 360 degrees without cropping, so it doesn’t matter which direction the helicopter is ultimately facing. I think it’s obvious that the final position isn’t exact in all these images. Wind, time constraints, and FAA instructions make hitting the same mark every time nearly impossible. But that doesn’t stop us from trying.

![]()

Second, there is the airspace clearance and ascent time. The pilot is in contact with TRACON (Terminal Radar Approach Control) well in advance for clearance and is on the radio constantly during the flight, coordinating with the local airport towers. The ascent to the location can sometimes take over half an hour, depending on the route the towers dictate, which is determined by which runway commercial airlines are utilizing. For example, on our two most recent flights, we spent 20 minutes ascending near Coney Island and then over 30 minutes out by Newark. These long ascents provide an opportunity to shoot some less-photographed areas of the region and zip up extra layers. The temperature on our last flight was in the 80s on the ground but dipped well into the 40s once we were at altitude. Fingerless gloves and a stocking cap are always at the ready for high-altitude flights regardless of the season.

![]()

We picked the project up again a few weeks ago with a midday flight and another during blue hour. Once we’re in position, it only takes a few minutes to get the shot. I tend to bracket the exposure and shoot at as deep of an f-stop as the light allows to make sure it’s sharp. This type of aerial photography is an incredibly expensive endeavor,r so there’s no time to review images. Knowing that the settings are correct and trusting your camera is the key to success. I always fly with multiple bodies as well; changing lenses is too dangerous when the doors are off, and safety is paramount. The body with the fisheye is wrapped and secured once this shot is complete, and then I switch to my 2nd and 3rd bodies for the descent down. My go-to general-purpose lenses are Canon’s 16-35 f2.8 and 70-200 f2.8. To be hones,t it’s pretty tough to take a bad picture from this viewpoint.

I’m pretty happy with this series thus far, but there’s definitely room for improvement. If you’ve ever wanted to get a different view of NYC, test out some new kit, or just take in the city at sunset from above, helicopter photography is always an incredible experience. It isn’t lost on me that it’s an absolute privilege to be able to do this professionally and I wouldn’t be in this position without the pilots and staff of FlyNYON. Hopefully, I have the opportunity for another high altitude flight this fall, I think a fisheye with Central Park in full autumn colors would really round out the series.

About the author: Taylor is a Brooklyn based filmmaker and cinematographer. After beginning his career in fashion as a digital tech and photo assistant, he moved into film production as an AC and has been working as a DP and Director since 2010. He has filmed on every inhabited continent in over 50 countries. Documentaries are his favorite projects to work on as well as the occasional music video. His hobbies include running marathons, repairing mechanical watches, skiing and anything that involves a passport.

Image credits: All photos © Taylor Scott Mason | website / Instagram

![[2025 Upgraded] Retractable Car Charger, SUPERONE 69W Car Phone Charger with Cables Fast Charging, Gifts for Men Women Car Accessories for iPhone 16 15 14 13 12, Samsung, Black](https://i1.wp.com/m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61SaegZpsSL._AC_SL1500_.jpg?w=300&resize=300,300&ssl=1)

![[True Military-Grade] Car Phone Holder【2024 Stronger Suction & Clip】 Universal Cell Phone Holder for Car Mount for Dashboard Windshield Air Vent Long Arm Cell Phone Car Mount Thick Case,Black](https://i2.wp.com/m.media-amazon.com/images/I/715PBCuJezL._AC_SL1500_.jpg?w=300&resize=300,300&ssl=1)

![[エレコム] スマホショルダー ショルダーストラップ 肩掛け ストラップホールシート付属 丸紐 8mm P-STSDH2R08](https://i3.wp.com/m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51BMFf06pxL._AC_SL1500_.jpg?w=300&resize=300,300&ssl=1)